Gustavo Aguirre Jr.

Story by Tara Lohan | Photography by Sarah Craig | Español

My car tails a blue Honda, decked with shiny rims and a glittery paint job that in the midday sun sparkles like a disco ball. It’s piloted by 27-year-old Gustavo Aguirre Jr. — he’s my tour guide for the day. He takes me on the ‘scenic’ route so I can see the aging pumpjacks of the Mountain View Oil Field, which sprung to life in 1930s. Most of the pumps are resting and rusting in dirt fields, as they have for decades. A few still labor up and down.

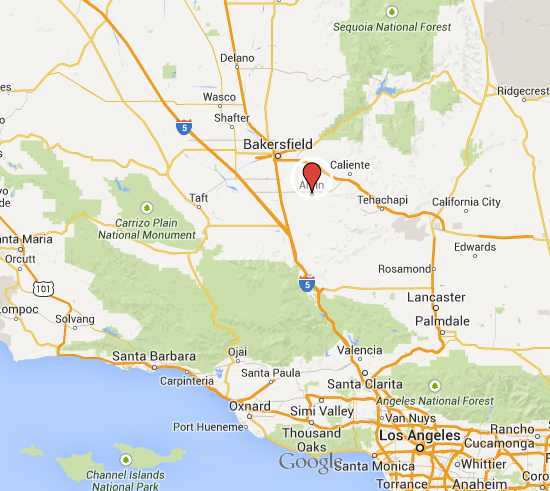

The oilfield underlies the town of Arvin near the southernmost part of Kern County in California’s Central Valley. Arvin is 15 miles southeast of Bakersfield and 100 miles north of Los Angeles. It’s hugged in a suffocating embrace by mountains on three sides, which trap the valley’s pollution. The day I visit I only see mountains on one side, they’re blurry, like an oil painting smudged before it dried. The other mountains have been entirely swallowed by the haze.

Part of Gustavo’s job is trying to figure out what exactly residents here are breathing. While he lives in Bakersfield, Gustavo works as an organizer with Global Community Monitor and in partnership with local organizations like Committee for a Better Arvin. They’ve set up air monitors in different places in town, trying to track the amount of particulates, ozone, and other pollutants. And they work to hold polluters accountable.

One thing could soon make Arvin’s air even worse, though. While Arvin’s oilfields have been mostly quiet since the 80s, Gustavo has seen the tell-tale sign that the sleeping beasts will be awakened: white pick up trucks. In oil country these are the ubiquitous ride of industry workers. The flurry of white pickups coming and going from the fields has Gustavo and the folks he works with on edge. And for good reason. Well simulation techniques like hydraulic fracturing (aka “fracking”) and acidizing, are being used across the state to squeeze more drops out of aging oilfields.

Arvin is a town at the tipping point. Likely beyond it.

This is actually the reason Gustavo is taking me on a tour. I’ve spent years documenting the impacts of fracking — visiting everywhere from small West Virginia “hollers” (hollows) to the boom towns of North Dakota’s Bakken shale. And now I want to know how fracking is affecting communities in my home state of California.

Bucket Brigade in Action

Gustavo has recently learned that chemicals common in fracking have already ended up in Arvin. But he’s still trying to figure out how. He knows that enough bad stuff already makes its way to Arvin — the town is frequently referred to as “overburdened.”

Los Angeles sends its sewage and garbage to a “recycling” facility in Arvin in what seems to residents like a nonstop caravan of diesel trucks. “On a good day you smell feces and burning plastic,” says Gustavo. I don’t ask what a bad day smells like. The town is also downwind from San Francisco, Sacramento, and other cities. And just for good measure, neighboring Lamont ships its wastewater to Arvin. Combine this with a surrounding county famous for oilfields, feedlots, and mega farms, and “overburdened” is clearly an understatement.

Arvin is a town at the tipping point. Likely beyond it.

To counter this Gustavo has helped to launch the “Bucket Brigade” — a group of community members who’ve been trained to take air samples (they literally use a bucket, outfitted with a special bag and hoses) when something seems particularly bad. Here’s an example: In March, residents who live on Nelson Court, just across the road from Arvin High School, were complaining about noxious odors that caused one pregnant resident to faint from the fumes.

Most people assumed the culprit was Southern California Gas, the local power company. But when the company tested its gas lines, they found no leaks. The offender actually turned out to be Petro Capital Resources, the sole oil company working in the area.

Petro Capital Resources insisted at first the pipeline wasn’t theirs — it wasn’t on any of their maps — and the county had no record of the pipeline either. The state’s Department of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources requires the regulation of pipelines that are four inches in diameter and larger. This one was three inches.

It turns out the pipeline was actually built in the 1970s on a lease that has since passed company hands numerous times, most recently to Petro Capital Resources in 2012. It’s not believed to have been safety tested. Ever. It may have been leaking for months or years. And there may be others. Gustavo explains that beneath Arvin is a web of pipelines, many of which are three-inch lines strung together avoiding regulation.

"Nelson Court Evacuation" by Faces of Fracking, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Residents along one side of Nelson Court — a total of eight houses — were told they should leave. At first the suggested evacuation didn’t have many takers. But soon after, a fire chief made it mandatory, telling residents that their houses were liable to ignite at any moment from gas build-up. Those living across the street were told they could stay.

A Crime Scene

Gustavo and I visit Nelson Court in June, two and a half months after the evacuation, and the eight homes have brown and weedy front yards. Yellow caution tape lines the length of the block, wrapped around fence posts and mailboxes. It looks like a crime scene. And it is — in more ways than one. A white security truck circles the block. Just about all the houses Gustavo says have been robbed, most stripped — one even of its 2,000 pound pool table. Most residents have been relocated to an apartment complex in Bakersfield 20 minutes away. Their teens still attend the high school across the street. They have no idea if and when they’re coming home. And apparently there won’t be much left when they do. (Update: Residents were allowed to return home on October 31, nearly eight months after being evacuated.)

Gustavo has been in frequent touch with the residents and has taken air samples with his bucket. “We found a who’s who of fracking chemicals,” he says about a sample taken three weeks after the leak was first confirmed. His sample turned up several chemicals which were listed in a Congressional report on the most frequent chemicals found in fracking fluids, including toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene. “From what we know there is no fracking in Arvin — so where the hell are they coming from?” Gustavo asks.

According to the report, all three (part of a group known as BTEX chemicals), are “a regulated contaminant under the Safe Drinking Water Act and a hazardous air pollutant under the Clean Air Act.” The Bakersfield Californian also reported a cocktail of 20 chemicals including methane, n-hexane, heptane, benzene (a known carcinogen), “along with toxic gas levels 13 times higher than levels deemed safe by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.” In two houses the concentration of explosives gases were found to be more than 50 percent, which makes it astonishingly lucky that the leak was discovered before anything more horrific occurred.

It turns out the pipeline that leaked under Nelson Court carried “field gas,” which is the waste that oil and gas companies can’t use and want to get rid of. It’s already full of petrochemicals and may also contain additional chemicals added during production and well stimulation (like fracking or acidizing).

This waste is then sent through pipelines to flares — tall, metal pipes, with an ignition that burn the gases off in a firey hiss. Igniting gases instead of releasing them into the air unburned causes less toxic emissions, although as I would soon find out, it doesn’t mean they’re completely benign. There are two flares that sit a few hundred yards from Nelson Court in a tomato field across from the high school.

Gustavo and I take a drive out to the closest flare. When we pull up I assume it’s not on; the one further afield has a bright flame shooting from it, but this one doesn’t. It’s not until I get out of the car that I hear it roaring and I can see a faint shimmer of emissions. It is pouring god-knows-what into the air at full force. I shout questions to Gustavo and hope my recorder is picking up his answers because I’m trying to stay focused on not throwing up. The flare’s emissions have me dizzy, sucker punched.

Back in the car we talk through where the chemicals may have come from that his air sample found on Nelson Court. Did they blow down the valley from some of the hundreds of wells being fracked elsewhere in the county? Or maybe the waste gas that is being piped below homes here or burned off in the flares came from nearby oilfields where fracking is common? It’s impossible to know.

Living Downwind

Most of the national conversations that happen around fracking discuss what goes at the well site and whether drinking water contained in underground aquifers can be contaminated by fracking chemicals injected beneath these water supplies. But what I’ve learned from visiting communities across the country, is that the impacts also end up far downstream and downwind. Determining how communities are affected by fracking means you have to follow the toxic air emissions and millions of gallons of wastewater after they leave the well site.

Arvin may be one of those places these pollutants go. “We took our results to the city and they said there is no fracking here, don’t worry about it,” Gustavo tells me, “But the citizens are worried about it. There is a potential they can’t return to home, if they can, how safe is it?”

It’s hard to assuage residents’ fear based on the words of government agencies that have largely failed the community already when it comes to public health. Besides, fracking has taken place for decades without regulation in California (the process of drafting regulations has only just begun in 2014), so who’s to say it hasn’t happened here, residents wonder. If officials didn’t know about the pipeline under their homes, what else don’t they know?

"A Flare Burns in Arvin" by Faces of Fracking, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The price of not knowing may be steep.

“There are times when I come out here and I get severe allergic reactions. I get rashes, really my nasal cavity has diminished so much,” says Gustavo. “There is very little odor I can smell now. I get irritation in the eyes and nose especially when I’m in that neighborhood where the fracking chemicals were found. My throat just swells up and gets really dry.”

Even though Gustavo doesn’t live in Arvin, he’s down here every week and sometimes every day. It’s clearly enough to be a health threat.

When the news media covers fracking-related disasters, it usually involves some type of fire — exploding water from kitchen faucets or derailed trains bursting into flames. But for Arvin, the most dangerous impacts are likely what you don’t see. It’s not one catastrophic event, but a slowly accumulating disaster.

It makes me wonder about the people who live here full time. Gustavo tells me there’s about 20,000 of them and 93 percent are Hispanic or Latino. Some residents trace their roots back to Basque sheepherders who arrived here during the Gold Rush, but most others have come across the United States’ southern border more recently from Mexico and Central America. The predominant language is Spanish and the leading employer is agriculture. Work is often seasonal and unemployment can be as high as 40 percent. Gustavo calls the residents “working class America” but they are more likely the (very hard) working poor — economically and politically disadvantaged.

“Overburdened” here is not a surprise.

Gustavo is well aware of the challenges Arvin’s residents face. He used to work as a farmworker organizer before joining Global Community Monitor eight months ago. He also grew up following seasonal crops as his parents worked in the fields, bouncing between Southern California ag towns like Oxnard, Indio, Blythe, and Coachella.

His father started organizing fellow workers and then got a fulltime job with the United Farm Workers, moving the family to Bakersfield when Gustavo was 13. They’ve remained there ever since.

Gustavo loves being an organizer, he says, despite being the only one of his friends not working in the oilfields. One of the best perks of his job is training a new army of citizen scientists, the Bucket Brigade, that fill the holes that local and state agencies either can’t or won’t.

Before I leave Arvin, Gustavo takes me to an air monitor he’s attached to a highway billboard that welcomes people to “Arvin, Garden in the Sun.” It’s directly across the street from the noxious “recycling” facility which has a shrine in front of it adorned with flowers and crosses commemorating two brothers, 22 and 16, undocumented workers who died of hydrogen sulfide poisoning while working there.

It’s a reminder that living here, and working here, is dangerous business. I ask Gustavo if he worries about his health. His supervisor, who works in Richmond, California in the Bay Area, he says, has sent him a gas mask. I hope he wears it.

I get back in the car to head to my home — also in the Bay Area. When I arrive I’m engulfed in thick summer fog that lasts until the next morning, which is just about when my nausea from Arvin’s flare begins to wear off. As the day heats up the fog burns off and I’m left with clear, blue skies. I inhale deep, guilty breathes as I think about Arvin and Gustavo’s ongoing work to lift its burden. I’m glad he’s not alone in his efforts. With the help of a 19-year-old city councilor who happens to live on Nelson Court, Gustavo’s coalition wants to pass a moratorium on fracking in Arvin.

It’s wildly unpopular among legislators in oil country. But the coalition doesn’t care. This is one thing they want to stop before it starts, says Gustavo. White pick up trucks be damned.

Tell others about this

Faces of Fracking is a multimedia project telling the stories of people on the front lines of fracking in California.