Rosanna Esparza

Story by Tara Lohan | Photography by Sarah Craig | Español

"Rosanna Visits Lost Hills" by Faces of Fracking, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Rosanna Esparza parks her Prius in a sea of pickups. Across the street a makeshift flagpole has been erected in a truck bed to hoist Old Glory above the palm trees. We’re in Taft, California; a town built on one of the largest oil fields in the country. It’s a fitting place for the local petroleum industry to hold an “appreciation rally” for itself.

At the front door of an auditorium inside the walled compound of the Taft Fort a few police officers question us. “We’re here to show our appreciation,” Rosanna says. They wave us through. The truth is though, we’re impostors. We are not here to applaud.

As a community organizer for Clean Water Action, Rosanna is the lone staff member outposted here in Kern County, which ranks first in the state for oil production and second for agriculture. To be any kind of an environmental organizer in this territory is brave.

As an environmental journalist I meet a lot of environmental organizers – it’s par for the course. But Rosanna is not like any I’ve come across before. She’s Latina, 59, from the Los Angeles area, and new to environmental organizing. In fact, she first came to Kern County to do ethnographic research for a PhD in gerontology.

She decided to stay because she saw a community in deep need of healing and she thought her expertise could help make a difference. She joined a church, started taking her dog, Mr. Luna, along with her to read to elementary school kids, and spends the bulk of her day challenging one of the most powerful industries in the world. She’s not the type to wield a bullhorn at the front of a protest, though. She’s more interested in making connections in the community than disrupting it. She won’t be unfurling any banners at this industry rally.

“There is a real misconception about what we do and what we are after,” says Rosanna. “I’m not looking to put people out of a job, I’m asking that you do what you do safer. You’ve got the money to do it, you’ve the technology, and the experts.”

I tracked Rosanna down because I want to understand what’s happening in Kern County — the epicenter of the oil industry in California. Kern County produces nearly 75 percent of California’s oil, but production peaked in 1985 — it’s been a slide ever since. The industry has one big, blank check they are still trying to cash, though. It’s from the Monterey Shale, a rock formation that encompasses 1,750 square miles of south-central California, and reaches a depth of 18,000 feet in some places. A 2011 report published by the U.S. Energy Information Agency said the Monterey held the largest shale oil deposit in the U.S. — a whopping 15.4 billion barrels. Industry has been trying to hit it big in the Monterey for years, and they’re trying every trick they know, including fracking.

This is the “resource curse,” where boom is followed by bust.

After years of writing about what fracking-induced oil and gas rushes look like in places like North Dakota, Colorado, Texas, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, I’ve turned my attention to my home state of California.

By now most people have heard about fracking — short for hydraulic fracturing. Industry has been applauded for using fracking, often in combination with horizontal drilling, to tap “unconventional” oil and gas reserves in shale — boosting domestic production. And industry has also come under attack because fracking is dirty and dangerous. You’ve likely seen the videos of people lighting their tap water on fire.

What I’ve mostly seen in my cross-country travels are communities dealing with snowballing impacts from fracking: air pollution, water pollution, spills, accidents, truck traffic, surges of transient workers, skyrocketing prices for affordable housing. The list goes on.

This is the “resource curse,” where boom is followed by bust. I’ve spent enough time in West Virginia mining towns to know how this plays out decades later.

Is California headed for the same fate? With Rosanna’s help, I want to understand what’s at stake. Kern County sits atop a potential gold mine and if it’s fully plundered the consequences could have a huge ripple across not just the state — but also the whole country.

Finding Lost Hills

When Rosanna wants to take stock of what she’s up against all she has to do is stand on the bluff at the aptly named Panoramic Park, near her home in Bakersfield. Stretched for miles below is the Kern River Oilfield. The first slurps of Pleistocene hydrocarbons were drawn here in 1899 and today it’s an apocalyptic 10,000 acres of pumpjacks, pipes, and boilers — the third largest oilfield in the state — now under the dominion of Chevron.

A jogging and biking trail inexplicably snakes the oilfield’s border and suburban streets dead end at its lip. It’s a jarring juxtaposition but also an important reminder: The oil industry and the community in Kern County are closely intertwined. Rosanna has learned this the hard way.

“A lot of the old west mentality still exists here,” says Rosanna. “So much of their verbiage is shoot ‘em up. ‘Drill here, drill now,’” she says, echoing the rallying cry we heard at the pro-industry rally in Taft.

When the ‘49ers switched their sights from gold to oil in the late 19th century they discovered what Native Americans had known for thousands of years — you could find oil (or oil-like substances) that bubbled to the surface in tar pits or seeps. Here nature flaunted its riches. Wells were sunk to mine the fortunes below and Kern County became one of the largest oil producers in the country.

It is also one of the biggest farming counties, too and part of the San Joaquin Valley where agriculture is a $40 billion a year empire. But in many ways life here is somewhat feudal. Big Oil and Big Ag are part of a wealth gap that feels like the Grand Canyon — an incomprehensible divide. Billion dollar companies operate in the county, while some communities have more than 40 percent of their population living below the poverty line — twice the state average. For all the riches extracted from the land and beneath its soil, this still remains one of the poorest parts of the state.

This reality is what drives Esparza’s work. Her time is often spent bouncing between the small agricultural communities in the valley – Shafter, Wasco, Lost Hills. Most of the folks that live in those towns are Hispanic or Latino, most are farmworkers. She is worried that these communities are already being crushed under the weight of environmental health burdens: Kern County ranked as having the most dangerous air pollution in 2009 and has drinking water contamination in many places.

Take Lost Hills, for example. This spring and summer Rosanna spent five months driving 102 miles round trip twice a week from her home in Bakersfield to the tiny community of Lost Hills on the far west side of the valley. The town is little more than a collection of low-income housing for workers employed by the agribusiness giant Paramount Farms (owned by the $3 billion company Roll Global).

Lost Hills also sits adjacent to the Lost Hills Oilfield – and is just off Route 33, also known as the Petroleum Highway, a stretch of road that contains half a dozen major oilfields. I’d driven the Petroleum Highway before I met Rosanna and dismissed the area as a dusty wasteland on the outskirts of the valley. I didn’t know there was anything out there that wasn’t part of the industry’s machinations. It turns out there are a couple thousand people and they’re not in good health.

Rosanna’s visits to Lost Hills were to collect health surveys of residents and their kids — the project is a collaboration between Clean Water Action where she works, and Earthworks.

“We’re asking individuals what the impacts [of living near an oil field] have been,” she explains. “How do they feel? How is it affecting their everyday lives? Do they have existing chronic conditions that are exacerbated because of living in the community?”

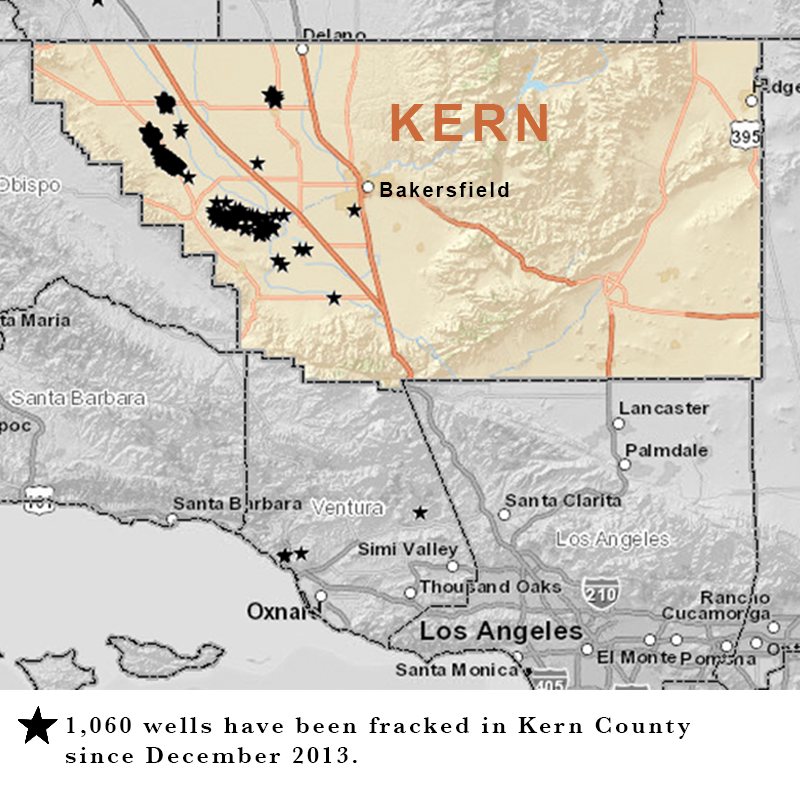

It turns out that at least 244 wells have been fracked in the Lost Hills field, most of them in the last two years. Some of the chemicals commonly used in fracking are known or suspected human carcinogens, and the health risks of many others are totally unknown. The practice also produces millions of gallons of toxic wastewater, which can contaminate surface water, groundwater, food sources, and release harmful chemicals into the air.

“We know that communities that are within five miles of unconventional drilling are more apt to experience headaches, nausea, vomiting, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and kidney diseases,” says Rosanna.

Big oil says they are not endangering the community, Rosanna adds. “We are learning that that is absolutely not true.” She’s found oil fields that buttress up against an elementary school playground and wastewater pits that sit a mere three feet from a public road. “These pits were the kind where when you walked up to them, all you had to do was count to 25 and you have a blazing headache,” from the fumes, says Rosanna.

Half the school-aged kids she’s interviewed suffer from headaches and nosebleeds. Some are missing school 40 percent of the time. And nearly half of adults have inhalers.

The conditions in Lost Hills can be brutal – for the people who live there, and those like Rosanna, who are crazy enough to visit. In the summer, temperatures top 115 degrees and sandstorms blow so hard you can’t drive.

The wind blows with it, not just sand but chemicals from agricultural fields and neighboring oilfields. At this point, it’s impossible to know if the people in Lost Hills are sickened by chemicals from agriculture or oil production – or some combination. “I fear for them — for their safety, for their health, and their children,” she says. But Rosanna’s collaborator, Jhon Arbelaez of Earthworks, is also taking air samples, trying to see if they can find the chemical fingerprint in the air that may help lead them to the source of people’s health woes.

“We could use some more people working out here,” Rosanna tells me, sounding exhausted from five months of blazing sun, blowing sand, and taking the pulse of sick town.

She’s discouraged they cannot pinpoint where residents’ health problems are coming from. But it’s a nearly impossible endeavor and it’s made more difficult by the fact that oil drilling companies who frack were only mandated at the beginning of 2014 to disclose the chemicals they use and they are exempt from major federal laws intended to protect public health. It won’t be until July 2015 that California will even have regulations in place for fracking.

I’m continually amazed that more studies are not done by health agencies and that such studies are in fact not mandated before drilling is allowed. For the all the hundreds of thousands of wells that have been drilled and fracked across the country, for all the thousands of communities that have been impacted, not a single comprehensive health assessment has been done. Ever. What are we afraid will be found?

When Rosanna tells me about her findings in Lost Hills, I think of a couple I know right now in West Virginia who are selling off their goats, finding homes for their cats, and packing up the contents of the house they built with their own hands. Ever since fracking began near them, the water they drink from their well gives them lumps in their necks.

They have no way of knowing if fracking is to blame. They can only suspect. Enough neighbors in their tiny community of a few dozen have died suddenly from cancer to make them afraid to stay. They are leaving with the heaviest of hearts, but still alive.

Many of the people who live in Lost Hills don’t have a lot of other options — they have limited income and job mobility. I feel for them and I’m amazed at Rosanna – she could be anywhere but she’s chosen to be there. To witness. To help.

Roses to Rigs

When Rosanna first moved to Kern County, the smell was welcoming, familiar. She came from Pasadena, home of the Rose Bowl, to tiny Wasco, where half of the country’s roses are grown.

Or they were, she tells me. In just six years she’s seen many of Wasco’s rose fields disappear. Rosanna takes me out looking for roses but mostly we see almond and pistachio orchards bulldozed to make room for drilling rigs.

Wasco is farmland cut into squares by wide, flat, gridded streets. It is similar to Shafter, just eight miles south. Both are farm towns in the middle of the San Joaquin Valley – the agricultural heart of the county. For a century, oil has been drilled on the east and west sides of this valley, but in the last few decades as the hunt for oil has intensified, drillers have moved into towns in the middle – next to homes, farms, and schools.

"Shafter Community Garden" by Faces of Fracking, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The Rose Oil Field under Wasco and the North Shafter Oil Field under Shafter were discovered in the 1980s, about a century later than most of California’s oilfields. Drillers seem to be making up for lost time here. And that keeps Rosanna busy.

She tries to keep track of rigs in the fields and whether they are fracking. Sometimes she takes air samples and logs complaints from residents. Wastewater has been illegally dumped into unlined pits here and flares burn toxic gases day and night.

At least 30 wells have been fracked recently in Wasco, and more than 31 wells have been fracked in the North Shafter Field in the last two years, some right next to Sequoia Elementary School. Lumbering horseheads of white and red oil pumps nod above the crops in the surrounding fields — more than 60 active wells ring a two-mile perimeter of the school.

“My daughter started with the headaches, when they started the work [on oil wells] over there” Rodrigo Romo, an area resident told me, pointing to a now producing well that sits just outside the school grounds. “The teacher didn’t want to have the recess outside. Outside it smelled like oil, it’s not good.”

Defending the Fort

Rosanna and I decide to visit the pro industry rally in Taft out of curiosity. A few months before she had organized a community viewing of the film Gasland 2 – a documentary critical of the fracking boom. Industry got wind of it and decided to fill the seats with their members to disrupt the showing. What was meant to be a public education event became a turf war. Angered, Rosanna told industry workers to get their own event.

Apparently they did.

Neither Rosanna nor I have ever been to a petroleum industry rally before and I have to admit, it was a little disappointing. There were more dress shoes than work boots. More state politicians who sent video taped platitudes from Sacramento than workers from the oilfields who stood up to speak. Mostly people sipped from bottled water, filled their plates with fruit slices and cheese cubes, and clapped politely.

There was some fist pumping and some jokes made at the expense of Prius owners. Rosanna tried not to look sheepish. And anyone who questioned the safety of fracking was dismissed as stupid.

Rosanna took it all in from the back of the room. Clapped a few times to not look too conspicuous and then we bolted as soon as it ended. “Let’s get out of here before they see my car,” she joked.

There was one thing that we both couldn’t help but notice during the rally. Industry seemed defensive, against the ropes. It’s possible they were reeling from news that came out a few months beforehand. In March the EIA amended its initial rosy predictions about the fortunes below Kern County. The amount of oil deemed recoverable in the Monterey Shale was slashed by an astounding 96 percent — from 15.4 billion barrels to a mere 600 million barrels.

"North Belridge Oil Field" by Faces of Fracking, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

If the Monterey or another formation doesn’t yield a big bounty soon, oil production here will continue to slide and that likely scares the pants off industry. And so does pressure from organizers like Rosanna who demand accountability. They are quick to silence anyone who raises questions, who voices concerns.

This is the opposite of how Rosanna was raised, and it grates on her. She believes everyone should get a say – and all voices should be heard. Her dad was raised by two Quaker sisters. “You don’t find too many Chicano Quakers,” she laughed. “It’s just not what we do.”

But Rosanna and her siblings grew up going to Quaker meetings in Pasadena. “We learned a lot about how things are done in a group, with consensus, with guiding principle,” she explained. “Even as a little kid you have a say. It’s probably the beginnings of how I became the person I am today. Everyone should have their say.”

This is the best antidote I’ve seen to the culture of silence and the lack of transparency that industry brings to their operations. The oil industry has shown their muscle in Sacramento — state senators who voted against a recent fracking moratorium were found to have received 14 times more money from the oil and gas industry and those who were in favor of the moratorium. Rosanna’s fight to make a difference here is not about who is louder, but how many voices join the conversation. The oil industry has the upper hand – the money and the friends in high places – but in the end it may not be the mighty but the many who win out in Kern County.

Tell others about this

Faces of Fracking is a multimedia project telling the stories of people on the front lines of fracking in California.